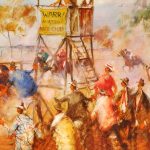

The First Glimpse (1995) – SOLD

Detail photos for this Artwork

In this drawing Hugh Sawrey records a pivotal event in naval and world history, the moment in Sydney on 20 August 1908 that Australians caught their first glimpse of the “Great White Fleet”, an armada of battleships from the United States Navy that sailed around the world on a friendly mission.

The Great White Fleet, a deployment of the US Atlantic Fleet to the Pacific, was the world’s first such movement of great battleships, and by far the largest and most powerful fleet that had ever circled the globe.

Initiated by then US President Theodore Roosevelt, the tour was intended to test his Navy’s professionalism, arouse popular interest in and enthusiasm for the navy, and demonstrate that the United States had arrived as a world power with a powerful navy. The tour was widely considered one of the greatest peacetime achievements in the US Navy.

The 14 month tour, which visited 20 ports on 6 continents over 14 months from December 1907 to February 1909, familiarized the 14,500 US naval officers with the logistical and planning needs for extended fleet action far from home and demonstrated America’s growing military power and blue-water capability. One goal was also to deter a threatened war with Japan since tensions were high in 1907.

Over half a million Sydneysiders turned out to watch the arrival of the fleet in Sydney Harbour. For a city population of around 600,000 this was no mean achievement and the largest gathering yet seen in Australia, far exceeding the numbers that had celebrated the foundation of the Commonwealth just seven years earlier.

No British battleship, let alone a modern fleet, had ever entered Australasian waters. Australian were treated to the greatest display of sea power they had even seen. The impressive armada was four miles long and consisted of 16 battleships divided into two squadrons, along with various small escorts. The Hulls of the ships were painted stark white, giving the armada its nickname.

The warm reception given to the naval crews during ‘Fleet Week’ in Sydney, was generally regarded as the most overwhelming response from any of the ports visited during the 45,000 mile global circumnavigation.

Interestingly, the epithet ‘Great White Fleet’ only came into popular usage during the fleet’s visit to Australia. During the fleet’s Sydney visit, The New South Wales government declared two public holidays, business came to a standstill and there was an unbroken succession of civic events and all-pervading carnival spirit in Sydney (followed by Melbourne and Albany) that severely tested the endurance of the American sailors! More than a few decided to take their chances and stay behind when the fleet sailed.

One man well pleased with the success of the Australian visit was Australia’s then Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, who had not only initiated the invitation to Roosevelt, but had persisted in the face of resistance from both the British Admiralty and the Foreign Office. By making his initial request directly to American diplomats rather than through Imperial English authorities Deakin had defied protocol, but he was also taking one of the first steps in asserting Australia’s post-colonial independence.

Deakin was, a strong advocate for the British Empire and Australia’s place within it, but he also wished to send a clear message to Whitehall that Australians were unhappy with Britain’s apparent strategic defence neglect.

The ships of Australia’s small, rarely seen and obsolescent Imperial Squadron based in Sydney did not inspire confidence, and highlighted Australia’s vulnerability to attack. Equally worrying and galling to local opinion, the unpopular Naval Agreement Act of 1903 meant that although Australia contributed £200,000 per annum for the Imperial Squadron’s upkeep, it could be withdrawn in times of danger to fulfil Imperial priorities.

To many this represented taxation without representation, but also highlighted how exposed and underprepared to attack Australia would be, being so isolated and vulnerable. The 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance (renewed in 1905), which allowed the Royal Navy to reduce its Pacific presence, did little to alleviate these fears. Remote from Britain’s European centre, Australians had no confidence that their interests would be accommodated in imperial foreign policy and reinforced the need for Australia to explore alternative security strategies.

Staunchly Anglophile, Deakin was not necessarily seeking to establish direct defence ties with the United States, but America with its growing presence in the Pacific, was the obvious replacement for Britain’s waning regional power. The United States possessed a similar cultural heritage and traditions, and as even Deakin took care to note in his letter of invitation to Roosevelt, “No other Federation in the world possesses so many features [in common with] the United States as does the Commonwealth of Australia.”

While the public admired the grand spectacle of the fleet’s visit, for those interested in defence and naval affairs it was an inspiration. This was part of Deakin’s plan, for although he was a firm believer in Australia’s maritime destiny, where defence was concerned national priorities still tended towards the completion of land rather than maritime protection. The Prime Minister’s own scheme for an effective local navy was making slow progress, and like Roosevelt he recognised the need to rouse popular support.

In this, the visit of the Great White Fleet played a crucial role, for it brought broader issues of naval defence to the fore and made very plain the links between sea power and national development. Americans clearly had a real sense of patriotism and national mission. Having been tested and hardened in a long and bitter civil war they were confident that the United States was predestined to play a great part in the world. Australians, on the other hand, still saw Federation as a novelty and their first allegiance as state-based.

Aiming to foster both national unity and spirit, Deakin used the Great White Fleet’s visit to demonstrate the community of feeling between the two nations as well as provide context for his own vision for a capable and recognisably ‘Australian’ navy.

Deakin’s party lost power before his plan could be set fully in motion, but he had laid the groundwork and established many of the essential elements. Most importantly, he had obtained Admiralty agreement to allowing full interchange of personnel between the British and Australian naval services. Without such unfettered access to technology and doctrine a local fleet would most likely become a wartime liability; with it the Australian Navy would achieve major economies in infrastructure and training.

In February 1909 the new Prime Minister, Andrew Fisher, placed orders in Britain for three 700 ton destroyers, the first of up to 24 similar vessels which would allow Australia to take responsibility for its own coastal defence. In July, the British First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, proposed that Australia acquire a ‘Fleet Unit’. Comprising a battlecruiser, several supporting light cruisers, and a local defence flotilla of destroyers and submarines, the ‘Fleet Unit’ represented an ideal force structure; small enough to be manageable by Australia in times of peace, but in war capable of efficient action with the imperial fleet. Moreover, it would be strong enough to deter all but the most determined adversary in local waters.

Parliament accepted the proposals and great efforts were thereafter expended to ensure that the navy would be a thoroughly and recognisably Australian force. On 4 October 1913 the first flagship, the battlecruiser HMAS Australia (I), and her escorts sailed into Sydney Harbour to a welcome no less enthusiastic than that accorded the Great White Fleet five years before. Just ten months later the fleet set out to face the harsh test of a brutal global war. For a newly acquired navy it was a remarkable achievement, and one which owed much to Deakin’s foresight.

Information courtesy of: Dr David Stevens, care of Royal Australian Navy website